Supporting the Creative Arts During a Global Pandemic

Figure 1: Jade Harland (2020), Canned Beans and Uncertainties, Acrylic on Paper.

Jade Harland

Monday 31 August, 2020

People across the country have already been significantly affected by Covid-19. Early reports are showing a concerning spike in numbers of people suffering from stress and other mental health issues. A recent study reported that 78% of participants say their mental health has worsened since the start of the pandemic (Newby, O’Moore, Tang, Christensen & Faasse 2020). Feelings of uncertainty and loneliness were reported as common amongst participants. Experiencing financial worries were also common and understandably considering the unemployment rate in Australia rose to 7.5%, the highest it has been in two decades (ABS 2020). The creative industries have been hit particularly hard. The majority of arts workers have not been able to apply for government support due to the nature of their work being contractual or freelance. The Australian Government’s response for the arts sector has been criticised by some for being too late and only supportive for large organisations (Caust 2020). If people are looking to the arts for entertainment during isolation whether it be from a book, film, music etc. how can we assure that the creators of such entertainment are supported and valued?

Arts organisations regularly must provide evidence and prove that their activities are of value in order to receive government funding. Despite the contributions from forms of counselling such as art therapy and the plethora of studies into the benefits of arts. Annual reports from the Australian Council and arts festivals such as the Adelaide Fringe, show the huge impact art has on tourism. In 2018, the Australian Council released findings from their study ‘International Arts Tourism: Connecting Cultures’, which showed that between the years 2013 to 2017, the percentage of art tourists rose to 47% which was higher than the percentage of international tourists overall at 37% (Australian Council 2018). International tourists are also more likely to attend arts events than organised sporting events, wineries and casinos (Australian Council 2019). The Adelaide Fringe released their annual report for 2020 which showed increased figures from 2019. Despite the event being affected in its last week due to the Covid-19 outbreak, the festival contributed $41.6 million dollars to the South Australian tourism sector which was an 8% increase on 2019 (Adelaide Fringe 2020).

Figure 2: Adelaide Fringe 2020, Blanc De Blanc, performance shot.

Although these figures will dramatically drop due to the Covid-19 travel bans, art has many other benefits. The arts also have social benefits by helping to bring communities together and promoting tolerance of other cultures. It allows individuals to interact and experience new cultures and can also provide them with a sense of identity (McCarthy, Ondaatje, Zakaras & Brooks 2001). One of my favourite examples of this is the group Conflict Kitchen, located in Pittsburgh, United States (Conflict Kitchen 2020). This is a restaurant which features different cuisines from countries which the United States is in conflict with. Each time they represent a new country, they also program events featuring performances and publications to encourage discussions and a better understanding of the featured culture. McCarthy et al. (2001) also outline how studies have shown that art can have benefits on cognition. Specifically, school aged children have shown that arts participation can improve their academic performance, improve basic skills and promotes creative thinking. It can also improve their attitudes towards the learning process. There are many arts organisations offering programs for arts participation in schools for example, this year the South Australian Living Artists Festival (SALA), established their ‘Schools Artists in Residence Program’. Local artists such as Thomas Readett hosted online workshops for students which resulted in a collaborative mural at their school. Another local artist, Louise Flaherty worked with the students at Lobethal Primary. They created a body of work which explored the local environment to learn about native plants and land (SALA 2020).

Figure 3. SALA (2020), Avenues College – installation shot, Acrylic Paint.

One of the most important benefits that art can offer is on our health and well-being. Studies have shown that it can improve quality of life for a range of patients including people suffering from Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, the mentally and physically handicapped and people who suffer chronic pain (McCarthy, Ondaatje, Zakaras & Brooks 2001). The arts have a significant role in promoting the mental health of participants. It can also help to challenge the stigma surrounding such issues (Quinn, Shulman, Knifton & Byrne 2011). In the UK, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing conducted a study ‘Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing’, during the years of 2015-2017 (Culture Health and Wellbeing 2018). This was not only to demonstrate the benefits on people’s health but to collate several recommendations for government to improve policies. The results from this inquiry show a plethora of statistics on how art can improve physical and mental health. Arts in health care environments alone can help to reduce sickness, anxiety and stress.

Many art programs and residencies are emerging in hospitals and health care settings. In 2017, I participated in an artist residency at Glenside’s Rural and Remote Inpatient Ward. This was organised through SALA, the University of South Australia and SA Health. The residency went for six months and during this time I made artworks alongside patients. The purpose was to discover if arts participation could aid the recovery process from a mental health illness. In my experience I learnt that patients were appreciative in having an impartial person to spend time with. Someone who was not interested in examining their health in anyway. I also found immense benefits to my own mental health in the process. The process of creating art formed a calm and safe space for all parties involved. Being a part of this filled me with a sense of purpose and knowing that art was able to help me connect with others validated my choice in career path.

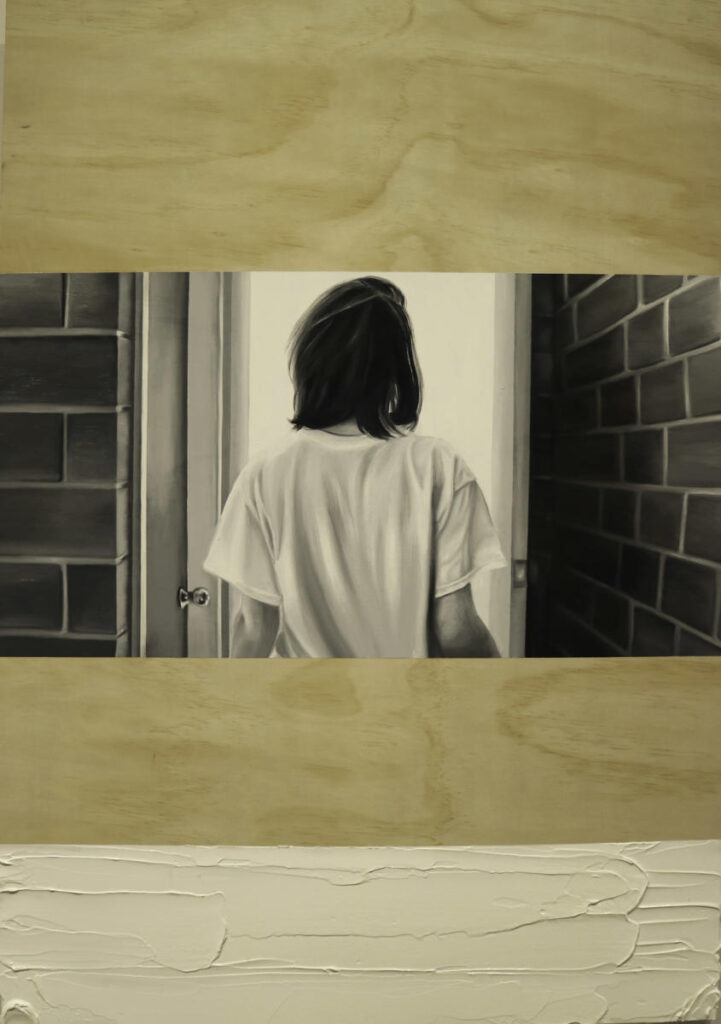

Figure 4. Jade Harland (2020), AM, Oil and impasto on wood.

As a visual artist I presume I suffer from similar struggles as most arts workers. I have a part time (non-arts) job which is my main source of income. I am constantly underpaid for art-related work. Applying for grants is a tiring task when the application process is complicated, lengthy and the competition is fierce. On top of these everyday struggles, artists not only lost work due to the pandemic, they were also told by the Australian Government that they were not regarded as essential workers. Sarah Borg, a clinical psychologist from Perth, discovered this was a common concern felt by a lot of artists from her program The Connection Project (Pickup 2020). The Connection Project was an online program where sessions were held for artists by three psychologists. The sessions were held for artists from anywhere in the world, to have a safe space to share and discuss any concerns they were facing. A similar online initiative was founded by Perth-based artist Alex Desebrock, who started the Facebook group Australian arts Amid Covid (Pickup 2020). What started out as a 300-member group intended for artist friends to stay connected, turned into an 18,000-member support network. It has allowed arts workers from an array of backgrounds to support each other and share advice on how to navigate their way through this new world. Digital initiatives like these will be essential for the near future. If there is not enough government support for individuals working in the arts, then they will need to look to each other for support and advice on how to navigate their way through this new world.

Figure 5. Tiffany Rysdale (2018), The Plant Stand, Oil on linen.

With the world facing so much uncertainty right now we run the risk of rising rates in depression and anxiety. People who are in isolation, needing a distraction or looking to make sense of it all, will look to the arts for answers. This will not be an option if artists cannot create due to lack of finances, resources or stress suppressing the creative juices. Artists are resilient, nimble and used to working with the struggles that come with any arts profession. However, we need these art communities to empower artists to encourage them to keep going. Despite the decades of research which proves unequivocally that art contributes economically, socially and benefits our physical and mental health, demonstrating this value appears to be an endless task. Perhaps if artists and organisations did not have to put time, money and resources into continuing this task, they could focus purely on creation.

References

Adelaide Fringe 2020, Annual Review 2020, viewed 20th August 2020, https://adelaidefringe.com.au/2020-annual-review

Adelaide Fringe 2020, Blanc De Blanc Encore, viewed 18th August 2020, https://adelaidefringe.com.au/fringetix/blanc-de-blanc-encore-af2020

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020, Labour Force Commentary, cat. no. 6202.0, viewed 10th August 2020, https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/7d12b0f6763c78caca257061001cc588/a8e6e58c3550090eca2582ce00152250!OpenDocument

Australian Council 2018, International arts Tourism: Connecting Cultures, viewed 20th August 2020, https://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/research/international-arts-tourism-connecting-cultures/

Australian Council 2019, Annual Report 2018-2019, viewed 20th August 2020, https://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/about/annual-report-2018-19/

Caust, J 2020, The arts needed a champion – it got a package to prop up the major players 100 days later, The Conversation, viewed 19th august 2020, https://theconversation.com/the-arts-needed-a-champion-it-got-a-package-to-prop-up-the-major-players-100-days-later-141444

Conflict Kitchen 2020, Conflict Kitchen Home, viewed 20th August 2020, https://www.conflictkitchen.org/

Culture Health and Wellbeing 2018, Creative Health:The Arts for Health and Wellbeing, viewed 20th august 2020, https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/

Jade Harland 2017, Gallery 2017, viewed 20th August 2020, https://jadeharland.com/gallery-2017/

Johnson, C 2019, ‘Art and mental health’, The Journal of Australian Ceramics, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 48–49.

McCarthy K, Ondaatje E, Zakaras L and Brooks A 2001, Gifts of the Muse: Reframing the Debate about the Benefits of the Arts, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica.

Newby JM, O’Moore K, Tang S, Christensen H and Faasse K 2020, ‘Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia’, PLOS ONE, Vol. 15, No. 7.

Pickup J 2020, Initiatives for connectedness and mental health for artists during COVID, ArtsHub, viewed 19th August 2020, https://www.artshub.com.au/news-article/features/covid-19/jo-pickup/initiatives-for-connectedness-and-mental-health-for-artists-during-covid-260876

Quinn N, Shulman A, Knifton L and Byrne P 2011, ‘The impact of a national mental health arts and film festival on stigma and recovery’, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, vol. 123, no. 1, pp. 71–81.

SALA 2020, Schools Artist in Residence Program, viewed 20th August 2020, https://www.salafestival.com/schools-artist-in-residence-program/

South Australia 2020, What to see and do at Adelaide Fringe, viewed 10th August, https://southaustralia.com/travel-blog/what-to-see-and-do-at-adelaide-fringe

Tiffany Rysdale 2018, Paintings, viewed 20th August 2020, http://www.tiffanyrysdale.com/paintings/